Graphic Adventures in Anthropology

This is the sixth post in a new blog series called Graphic Adventures in Anthropology. Once a week for several weeks, a guest contributor will write about some aspect of graphic anthropology (and by “graphic” we mean drawing in general, and comics in particular), from visual culture to visual communication, and from ethnographic method to dissemination device, culminating in the announcement of a new series we are launching at the press called ethnoGRAPHIC. Here’s the line-up:

Andrew Causey: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method

Stacy Leigh Pigg: Learning Graphic Novels from an Artist’s Perspective

Sherine Hamdy & Mona Damluji: Reflecting on Arab Comics: 90 Years of Visual Culture

Coleman Nye: Teaching Comics in a Medical Anthropology & Humanities Class

Gillian Crowther: Fieldwork Cartoons Revisited

Juliet McMullin: Comics in the Community

Nick Sousanis: Unflattening Scholarship with Comics

Anne Brackenbury: ethnoGRAPHIC: A New Series by University of Toronto Press

See last week’s blog posting here.

Fieldwork Cartoons Revisited

By Gillian Crowther, Capilano University

In 1989 when conducting fieldwork in Masset, Haida Gwaii, I complemented my standard social anthropological toolkit of camera, cassette tapes (before the days of digital), and field notebooks with a small black sketchbook—my cartoon book. This proved to be a rewarding and useful means to tell an immediate story about fieldwork, drawn late at night, and before any photographs could be developed. I used the cartoons to start conversations with Haida community members, and we shared perspectives on the events I depicted—from the ordinary to the celebratory. After returning from fieldwork and during the “writing-up” process, my thesis adviser, Paul Sant Cassia, encouraged me to submit my cartoons to the department’s journal, Cambridge Anthropology (1990). These were later cited by Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy in Rethinking Visual Anthropology (1997:n6:32) as a rare example of using a non-written, non-mechanical visual representation of ethnography. How exciting it is now, over two decades later, to have a chance to revisit these cartoons and situate them within broader anthropological concerns of learning to look and represent everyday life.

In 1989 when conducting fieldwork in Masset, Haida Gwaii, I complemented my standard social anthropological toolkit of camera, cassette tapes (before the days of digital), and field notebooks with a small black sketchbook—my cartoon book. This proved to be a rewarding and useful means to tell an immediate story about fieldwork, drawn late at night, and before any photographs could be developed. I used the cartoons to start conversations with Haida community members, and we shared perspectives on the events I depicted—from the ordinary to the celebratory. After returning from fieldwork and during the “writing-up” process, my thesis adviser, Paul Sant Cassia, encouraged me to submit my cartoons to the department’s journal, Cambridge Anthropology (1990). These were later cited by Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy in Rethinking Visual Anthropology (1997:n6:32) as a rare example of using a non-written, non-mechanical visual representation of ethnography. How exciting it is now, over two decades later, to have a chance to revisit these cartoons and situate them within broader anthropological concerns of learning to look and represent everyday life.

I began drawing short cartoon strips as an anthropology undergraduate in London, where I was learning about looking and thinking about culture and the sense the discipline had made of the world’s diversity. From all of our readings I was particularly taken by Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922:20). It was a long way from my upbringing in small-town Wales and I loved his exhortation to consider “the imponderabilia of actual life.” I could not be transported to an exotic island, nor was I writing an ethnography (or so I thought), but I could draw, and so instead I turned to graphically documenting my undergraduate life. I now realize I was exploring the dynamic of the insider/outsider perspective, and learning to tell a story and celebrate the significance of the ordinary. These cartoons depicted life in shared student accommodations, the friendships, relationships, adventures, and mundane activities, such as shopping, and bus journeys. These were also immediate, shown, and talked about, documenting our existence, in a format that really required looking closely, and seeing the place, things, and the moment that appeared to condense where we were at. Some cartoons worked, and others did not, but we did talk through them—a method I employed later in Masset, when I really was writing an ethnography.

Many of today’s undergraduates have no qualms about recognizing the worth and power of drawing a fieldwork scene. For instance, I have found this willingness showcased in undergraduate mini-fieldwork assignments, whereby the students spend two hours observing and then describing a place. At least two students per set of papers will accompany their written account with a drawing, attempting to capture the place and transitory moments of observation. The ability to see clearly, and to carefully note the surroundings whilst identifying cultural patterns, is a hallmark of anthropological research, and these papers combining text and drawn images often offer more depth and life to the observations. One student, who is known as “Ay V.,” has taken the use of graphics further, presenting her graduating project as a graphic novel, Green Tea Philia. This draws upon the work of Sidney Mintz (1985) and Richard Wilk (2006), and explores the rise of bottled green tea as symptomatic of our changing relationship with the environment and food. Ay V. conducted a short spell of fieldwork at the Unist’ot’en protest camp in Wet’suwet’en territory, British Columbia, where she spent time talking and drawing with local First Nations and activists trying to protect the land from pipeline developments. Her style draws upon Japanese, Celtic, Greek, and First Nations mythological characters, deliberately presented as cute food commercial cartoons, but peddling a serious environmental message. Her work is still on-going.

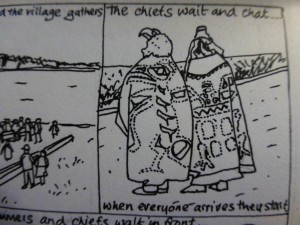

Cartoon strips and graphic novels push the methodological and representational boundaries of how culture is communicated, and demonstrate how anthropological understanding allows for many levels of interpretation. Each reading/viewing of the drawings allows for discovery, connections, and questions to be formulated, making understanding very active, whilst also guided by the creator’s frame and interpretation. I can now sit in my armchair, away from the field, and revisit the cartoon strips I created in 1989, and see new nuances of Haida culture that otherwise would fade: an elder’s comment about the smell of fresh cedar bark, the stance of hereditary chiefs as they wear their ceremonial regalia, and moments of quiet but powerful speech-making in the midst of community events. To return to these images recalls Malinowski’s (1926:17) cosy invitation to “step outside the closed study of the theorist into the open air of the anthropological field” to witness Haida experiences again, and rather than follow a “mental flight” back, the drawings can conjure a new form of ethnographer’s magic.

Cartoon strips and graphic novels push the methodological and representational boundaries of how culture is communicated, and demonstrate how anthropological understanding allows for many levels of interpretation. Each reading/viewing of the drawings allows for discovery, connections, and questions to be formulated, making understanding very active, whilst also guided by the creator’s frame and interpretation. I can now sit in my armchair, away from the field, and revisit the cartoon strips I created in 1989, and see new nuances of Haida culture that otherwise would fade: an elder’s comment about the smell of fresh cedar bark, the stance of hereditary chiefs as they wear their ceremonial regalia, and moments of quiet but powerful speech-making in the midst of community events. To return to these images recalls Malinowski’s (1926:17) cosy invitation to “step outside the closed study of the theorist into the open air of the anthropological field” to witness Haida experiences again, and rather than follow a “mental flight” back, the drawings can conjure a new form of ethnographer’s magic.

References

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1966 (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul Ltd.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1926. Myth in Primitive Psychology. London: Norton.

Mintz, Sidney. 1985. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin.

Wilk, Richard. 2006. Bottled Water: The Pure Commodity in the Age of Branding. Journal of Consumer Culture. 6(3):303-325.