Graphic Adventures in Anthropology

This is the fifth post in a new blog series called Graphic Adventures in Anthropology. Once a week for several weeks, a guest contributor will write about some aspect of graphic anthropology (and by “graphic” we mean drawing in general, and comics in particular), from visual culture to visual communication, and from ethnographic method to dissemination device, culminating in the announcement of a new series we are launching at the press called ethnoGRAPHIC. Here’s the line-up:

Andrew Causey: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method

Stacy Leigh Pigg: Learning Graphic Novels from an Artist’s Perspective

Sherine Hamdy & Mona Damluji: Reflecting on Arab Comics: 90 Years of Visual Culture

Coleman Nye: Teaching Comics in a Medical Anthropology & Humanities Class

Gillian Crowther: Fieldwork Cartoons Revisited

Juliet McMullin: Comics in the Community

Nick Sousanis: Unflattening Scholarship with Comics

Anne Brackenbury: ethnoGRAPHIC: A New Series by University of Toronto Press

See last week’s blog posting here.

Teaching Comics in a Medical Anthropology and Humanities Class

By Coleman Nye, Brown University

True or false: Stick figures effectively convey complex emotions and experiences.

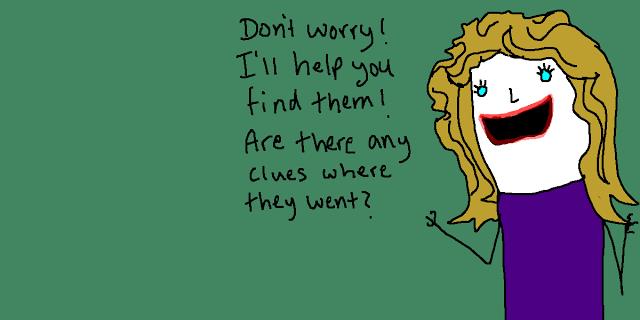

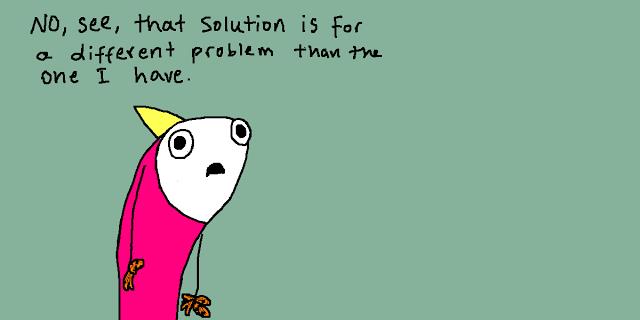

If you were to ask me this question a year ago, I would have confidently replied “false.” That was before I stumbled across Allie Brosh’s web comic “Hyperbole and a Half.” Brosh chronicles her adventures with cleaning, dogs, and depression through a crudely drawn pink stick figure with a strange yellow triangle atop her head. The triangle is supposed to be a ponytail, but it is open to interpretation. According to Brosh, “It is totally fine to think of it as a shark fin or a party hat” (NPR interview October 29, 2013).

It would not be an exaggeration to say that I was overwhelmed by Brosh’s graphic depiction of her depression. I followed this absurd little avatar across the panels, moving with her through feelings of desperate inertia, incomprehensible sadness, and oppressive self-hatred until she ended up with no feelings at all. I was deeply moved by this comic, and was stunned by its ability to communicate the depth, complexity, and loneliness of Brosh’s illness experience. It is difficult to fully comprehend the lived dimensions of someone else’s suffering. This is particularly true in the case of emotional and psychological pain. In the context of depression, the causal mechanisms are often far from clear and many of the signs of suffering are not easily apparent, often lurking beneath the surface. Yet, Brosh’s comic powerfully rendered her depression visible and tangible. In the squiggle of a grimace and buggy weepy eyes, I saw close friends, loved ones, even myself. Depression wasn’t some inchoate, vague thing. It was achingly real.

Stirred by the visceral quality of Brosh’s work, I decided to incorporate “graphic pathographies”—graphic novels and comics about illness experience (Green and Myers 2010)—into my upper-level undergraduate anthropology course, “Medical Humanities.” Geared toward pre-med students, the class examines the multifaceted relations between biomedicine, culture, and the art of care, and places a special emphasis on how creative and humanistic approaches to illness and healing might enrich clinical practice.

Stirred by the visceral quality of Brosh’s work, I decided to incorporate “graphic pathographies”—graphic novels and comics about illness experience (Green and Myers 2010)—into my upper-level undergraduate anthropology course, “Medical Humanities.” Geared toward pre-med students, the class examines the multifaceted relations between biomedicine, culture, and the art of care, and places a special emphasis on how creative and humanistic approaches to illness and healing might enrich clinical practice.

Before launching ourselves into the world of comics and medicine, we first read key texts in anthropology that address the importance of story in the work of biomedical diagnosis and patient experience. Through Byron Good’s Medicine, Rationality, and Experience, we considered how biomedical practitioners construct their objects of intervention by distilling the narrative of a disease—a biological disorder—from the patient’s more complex and messy account of their symptoms. Drawing on Arthur Kleinman’s The Illness Narratives, we then contemplated the impoverishment of biomedical discourses when it comes to accounting for the lived aspects of illness. The clinical sciences, writes Kleinman, “possess no category to describe suffering, no routine way of recording this most thickly human dimension of patients’ and families’ stories of experiencing illness” (1988: 28). These readings allowed us to consider what gets excluded from biomedical models of disease, to take seriously the work of narrative in clinical practice, and to privilege patient accounts of illness experience as key forms of knowledge and evidence.

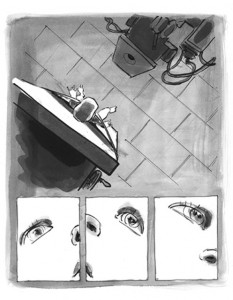

We began our venture into comics with David Small’s autobiographical graphic novel, Stitches. This stunning, cinematic piece of work chronicles Small’s painful upbringing, marked by illness, silence, and rage. Many students expressed surprise at the absorptive quality and visceral impact of Small’s graphic work. In the first day on the book, we drew on Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics to unpack the powerful sensorial effects of combining text and image, the ways gutters (spaces between panels) ask the reader to do interpretive and inferential work as they move from one panel to the next, how embodiment, emotion, and gesture are vividly depicted and often magnified through drawings, and how “cartoony” faces are strikingly neutral and empathic, enabling more readers to identify with the character’s experience.

We began our venture into comics with David Small’s autobiographical graphic novel, Stitches. This stunning, cinematic piece of work chronicles Small’s painful upbringing, marked by illness, silence, and rage. Many students expressed surprise at the absorptive quality and visceral impact of Small’s graphic work. In the first day on the book, we drew on Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics to unpack the powerful sensorial effects of combining text and image, the ways gutters (spaces between panels) ask the reader to do interpretive and inferential work as they move from one panel to the next, how embodiment, emotion, and gesture are vividly depicted and often magnified through drawings, and how “cartoony” faces are strikingly neutral and empathic, enabling more readers to identify with the character’s experience.

In our second day, we discussed Stitches alongside articles about the use of comics in medical education (Green and Myers 2010; McGrath and Watson 2013). By connecting some of the formal dimensions of comics with their educational potential, we asked: how might graphic pathographies increase doctors’ empathy, improve their observational and communication skills, and increase awareness of the social dimensions of disease? We analyzed how Small’s use of imagery forcefully conveyed the lived dimensions of disease in ways that text alone could not: the fear of a small child undergoing radiation, the importance of imagination and fantasy in coping with suffering, the damage done by having information about his cancer diagnosis withheld, and the confusion, isolation, and fury that attended the loss of his voice after a surgery severed his vocal cord. These vignettes from Small’s story fleshed out the physical and social complexities of suffering and offered a window into patient experience in a highly accessible format.

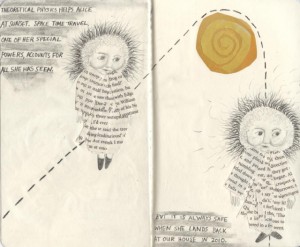

We then turned to how comics might address broader cultural questions regarding personhood and care through a case study in Alzheimer’s disease. Pairing medical anthropologist Dana Walrath’s whimsical exploration of her mother’s illness in her graphic novel Aliceheimers and TEDx talk “Comics, Medicine, and Memory” with Janelle Taylor’s article “On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia,” we asked: how might comics be a uniquely generative communicative medium for those without words? Graphic storytelling does important social work to connect caregivers with loved ones through image-based stories. It can also help to revise the dominant cultural narrative that equates the loss of memory and language with the loss of personhood. Through Walrath and Taylor, it became clear that comics offer a space to meet others in their reality, rather than forcing them into our own. Through pictures, we can devise a different “common sense” in which time travel is acceptable (why can’t Walrath be in 2010 while her mother is in 1945?), the self isn’t determined by memory, and meaning is conveyed without words.

We then turned to how comics might address broader cultural questions regarding personhood and care through a case study in Alzheimer’s disease. Pairing medical anthropologist Dana Walrath’s whimsical exploration of her mother’s illness in her graphic novel Aliceheimers and TEDx talk “Comics, Medicine, and Memory” with Janelle Taylor’s article “On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia,” we asked: how might comics be a uniquely generative communicative medium for those without words? Graphic storytelling does important social work to connect caregivers with loved ones through image-based stories. It can also help to revise the dominant cultural narrative that equates the loss of memory and language with the loss of personhood. Through Walrath and Taylor, it became clear that comics offer a space to meet others in their reality, rather than forcing them into our own. Through pictures, we can devise a different “common sense” in which time travel is acceptable (why can’t Walrath be in 2010 while her mother is in 1945?), the self isn’t determined by memory, and meaning is conveyed without words.

We ended our exploration with Allie Brosh’s web comics “Adventures in Depression” and “Depression Part Two.” One aspect of the comic that the students found most striking was her explanation of the jarring disconnect between her own crushing experience of depression and her friends’ attempts to help. “It would be like having a bunch of dead fish, but no one around you will acknowledge that the fish are dead,” writes Brosh. Students who had lived through depression firsthand found that Brosh’s “dead fish” sequence distilled and validated their experience. One student shared this comic with family and friends in an effort to communicate what she needed in terms of support. Another said that Brosh’s use of humor and honesty in her stick figure drawings helped to de-stigmatize depression, and provided an opportunity for her to reframe her own suffering as a valid and even communal way of being in the world, rather than a personal failure.

For their midterm assignment, I asked the students to create an illness narrative and provide anthropological analysis within the narrative or as a separate reflection paper. Many students made comics, which proved to be both analytically sharp and emotionally resonant. For example, one student developed a choose-your-own-adventure style comic book about the process of diagnosing and managing her depression. The reader could flip through comic scenarios that reflected different explanatory models, frustrations, and outcomes (or a lack thereof). This format made it possible for her to sit with the complexity of her experience, to trace connections and contradictions, to imagine alternatives, and to multiply her reality. In the conclusion of her reflection paper, she wrote, “[Drawing] allows me to acknowledge the humor, pain, absurdity, and suffering, while reaffirming the fact that I will, ultimately, be okay.”