Part of my job as an editor is to convince people to write the books I think they should write, not necessarily the ones they want to write. I’ve had some success doing so, even in the face of laughter, eye rolling, and outright rejection. In fact, some of the best books I have published came from authors who had originally put up the most resistance to my pitch. So perhaps it’s not surprising that I thought I could launch a new book series based on what some might call a wacky idea, without an academic series editor, and with no projects in hand.

That series, now known as ethnoGRAPHIC (ethnography in graphic form), didn’t come out of nowhere. I had to first learn to love comics, which didn’t happen until comics took more of a literary turn. I wasn’t really drawn to superheroes (though I have learned to love them in recent years) as much as comics that offered stories about people in their everyday lives, but in the context of a larger set of stories, a culture if you will. Comics like Persepolis, Fun Home, Building Stories, and Essex County.

That series, now known as ethnoGRAPHIC (ethnography in graphic form), didn’t come out of nowhere. I had to first learn to love comics, which didn’t happen until comics took more of a literary turn. I wasn’t really drawn to superheroes (though I have learned to love them in recent years) as much as comics that offered stories about people in their everyday lives, but in the context of a larger set of stories, a culture if you will. Comics like Persepolis, Fun Home, Building Stories, and Essex County.

As I delved more deeply into comics, anthropology was taking its own “arts” turn. In the years following the Writing Culture critique, anthropology turned towards more experimental forms of ethnographic method and representation—from poetry and fiction to creative non-fiction, as well as more visual forms like the films done by the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard and Philippe Bourgeois’ Righteous Dopefiend, which combined photography with dialogue and analysis to bring the life of homeless heroin users to the attention of a broader public.

What was happening in anthropology was an attempt to capture the complex nuances of what was going on in the field. It wasn’t about empirically deciphering patterns and principles, but what Michael D. Jackson described as “a fascination for the mysterious, emergent, and conflicted character of all human relationships.”

It wasn’t a huge leap then to put these two developments together. The way comics lent itself to both narrative AND a kind of visceral relaying of the more affective elements of ethnographic research made for a good fit. Add to that the feedback I had gathered from instructors about students’ resistance to reading regular ethnographies (no matter how well written) and their desire for more visual material, and this all seemed like such a great idea I wondered why no one had thought of it!

Turns out, I wasn’t a genius—there were a lot of people making this connection as well. Comics was making deep inroads into the academy in a variety of disciplines. But it was a conversation with Stacy Leigh Pigg in Vancouver well over five years ago, in which we talked about the specific potential of a collaboration between comics and ethnography, that helped me move from hunch to viable and testable hypothesis. After that conversation, I tested out the idea of ethnoGRAPHIC on many anthropologists. Over and over again, I met the same response: a kneejerk excitement, followed by skepticism, and ending with “it’s a great idea but it’ll never happen.” I knew the idea had real potential, but I was going to have to build it before people would sign on.

The emerging Graphic Medicine community, as well as the role that Penn State University Press played in supporting it, was not only inspirational, it showed me that a university press could publish actual comics, not just monographs or collections about comics. Connecting with Nick Sousanis and hearing about the impending publication of his comic dissertation, Unflattening, by Harvard University Press, and consulting with local illustrator and comic artist Nick Craine, gave me the confidence to pitch the idea of ethnoGRAPHIC to my editorial board.

So much scholarship had already been done by people like Hillary Chute and Bart Beatty among others, and by publishers like the University of Mississippi Press, that it wasn’t hard to sell comics as a serious endeavor. But it was harder to sell a series with academics actually working in the comics medium. With the help of Joshua Barker, an anthropologist at the University of Toronto who graciously agreed to act as Series Editor, and the support of my own publishing committee at the press, the series was formally approved in 2014. Now all I needed was a willing author and a book project!

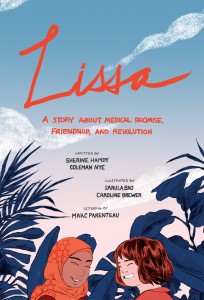

It wasn’t long before I came across Sherine Hamdy’s piece in a “Top of the Heap” column on the Somatosphere blog in which she mused whether a “graphic medical anthropology could bring medical anthropological and bioethical insights into more public engagement?” I phoned Sherine and the rest, as they say, is history. She had already written a fictional graphic novel script but was open to the idea of doing something that was more pedagogically oriented. We were both new to this, but there was such good will on both sides that I had a hunch it was going to work. By the time I met Sherine in person 6 months later, she had already talked with her co-author, Coleman Nye, about a project, found some early funding, and put out a call for artists at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

It wasn’t long before I came across Sherine Hamdy’s piece in a “Top of the Heap” column on the Somatosphere blog in which she mused whether a “graphic medical anthropology could bring medical anthropological and bioethical insights into more public engagement?” I phoned Sherine and the rest, as they say, is history. She had already written a fictional graphic novel script but was open to the idea of doing something that was more pedagogically oriented. We were both new to this, but there was such good will on both sides that I had a hunch it was going to work. By the time I met Sherine in person 6 months later, she had already talked with her co-author, Coleman Nye, about a project, found some early funding, and put out a call for artists at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

Nearly three years after that initial phone call, Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution will formally launch the ethnoGRAPHIC series. Whether it succeeds as a graphic novel and as an experimental ethnography will now be up to you to judge. But the sheer scope of the project is nothing less than inspirational. It’s a collaboration on numerous levels, experimental in form, and creative to the core. Much ink will be spilled about Lissa—including on this blog—in the coming weeks so I won’t add to that. Instead, I thought I would leave you with a few thoughts on what I see as the goals behind the series and its potential for injecting new energy into anthropology and ethnographic research.

Goal 1

To use the graphic narrative format to think through some theoretical and methodological issues in anthropology—representation, collaboration, ethics, participant observation, etc. And to involve informants in the research process in a more “visible” way, both literally and figuratively, including in the dissemination of the results of that research.

Comics offer what I think of as a more democratic opportunity for informants and research subjects to influence and understand the work of academics. Drawing and comics often appear more approachable and more obviously subjective than both photography and film (even if it’s not really the case), and informants often feel more comfortable giving their input on how events, perspectives, and people are represented. Because they usually tell stories in a sequential narrative, or can concretize a theoretical concept in a way that is instantly graspable, they are less intimidating than text-heavy books. Most importantly, at the end of the day, a graphic novel or comic may be far more useful to the community than a research report, book, or journal article. When people can literally “see” themselves in a comic, they are instantly invested. Finally, there is something about the physicality and durability of a print comic that lends both legitimacy and longevity to that research. It won’t be lost somewhere in the wilds of the endless internet, but found on a shelf for future generations to discover.

Goal 2

To use the graphic narrative format as a way of building understanding across cultural, class, ideological, and disciplinary divides.

Anthropology has always been about making the strange familiar and the familiar strange. Comics pair exceedingly well with this mission. Because comics rely on a set of visual signifiers that we all understand, a common language can be built quickly and easily integrating both difference and similarity simultaneously. Even the most foreign looking character, set in the most exotic locale, praying in a most unfamiliar manner can be made immediately familiar to us in the lift of an eyebrow, the shifting of feet, or in a yearning look that gestures at unstated hopes and fears. And that’s fertile ground for building connection across difference.

Goal 3

To contribute to a public anthropology by bringing contemporary anthropological research to a broader audience, especially students.

Anthropology, more than many disciplines, understands that theory and narrative can combine to create what Carole McGranahan has referred to as theoretical storytelling, a recognition that storytelling is a theoretical contribution in its own right and that privileging narrative does not mean giving up on theory. That said, understanding that stories are based on research, and are not concocted out of thin air, is important to convey to readers. Every book in the ethnoGRAPHIC series will offer a graphic narrative that stands fully on its own. But every book will also include extra material to profile the research underlying it, and to support its use as a pedagogical tool. This might include a teaching guide, a discussion about comics as a methodology, primary documents culled from research, links to further sources, etc. In this way we hope that while the graphic narrative engages new and existing readers, there will also be built-in support for encouraging deeper and richer discussions.

Goal 4

To create a space for collaboration, creativity, and experimentation for anthropologists, artists, and anthropologist-artists.

It may have been naïve of me to think it was possible to add another layer of collaboration onto what already happens between ethnographers and informants in the field. And yet this wasn’t just about wanting to capture a different kind of research, or bringing that research to a broader audience. It was also about providing opportunities for ethnographers to work more creatively themselves. No longer holed up in a room alone writing for hours on end, authors and comic artists can share, push, pull, and compromise as necessary in the pursuit of their goal. The tension that arises out of this process isn’t always easy. It’s full of questions about what to leave out, what works narratively and aesthetically, but also about how to ensure the integrity of the research and of those being represented. I’m convinced, however, that it can be a highly productive tension that results in something larger than either party might have produced on their own.

Anne Brackenbury

Executive Editor