Graphic Adventures in Anthropology

This is the seventh post in a new blog series called Graphic Adventures in Anthropology. Once a week for several weeks, a guest contributor will write about some aspect of graphic anthropology (and by “graphic” we mean drawing in general, and comics in particular), from visual culture to visual communication, and from ethnographic method to dissemination device, culminating in the announcement of a new series we are launching at the press called ethnoGRAPHIC. Here’s the line-up:

Andrew Causey: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method

Stacy Leigh Pigg: Learning Graphic Novels from an Artist’s Perspective

Sherine Hamdy & Mona Damluji: Reflecting on Arab Comics: 90 Years of Visual Culture

Coleman Nye: Teaching Comics in a Medical Anthropology & Humanities Class

Gillian Crowther: Fieldwork Cartoons Revisited

Juliet McMullin: Comics in the Community

Nick Sousanis: Unflattening Scholarship with Comics

Anne Brackenbury: ethnoGRAPHIC: A New Series by University of Toronto Press

See last week’s blog posting here.

Comics in the Community

By Juliet McMullin, University of California, Riverside

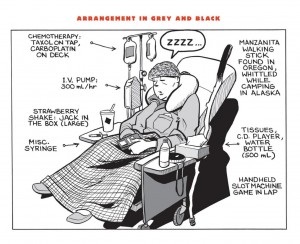

It all started with the May 2006 LA Times Book Review, and a comic panel of Brian Fies’ mom receiving chemotherapy. Fies’ panel, entitled “Arrangement in Grey and Black,” from his comic Mom’s Cancer, shows his mother sleeping while receiving chemotherapy. At the time I considered the panel as another artifact of cancer’s culture. But the image never left me. After well over a decade writing about cancer inequalities and seeing a series of cancer comics (fotonovelas, public health messaging, educational comics, and pink ribbon fundraising), I had not come across a story that was so honest and intimate. While there are a plethora of examples of comics in the community for health messaging, there are fewer examples of how comics can build community.

It all started with the May 2006 LA Times Book Review, and a comic panel of Brian Fies’ mom receiving chemotherapy. Fies’ panel, entitled “Arrangement in Grey and Black,” from his comic Mom’s Cancer, shows his mother sleeping while receiving chemotherapy. At the time I considered the panel as another artifact of cancer’s culture. But the image never left me. After well over a decade writing about cancer inequalities and seeing a series of cancer comics (fotonovelas, public health messaging, educational comics, and pink ribbon fundraising), I had not come across a story that was so honest and intimate. While there are a plethora of examples of comics in the community for health messaging, there are fewer examples of how comics can build community.

Intrigued by the idea of how to bring community into the growing conversation about comics, I heard a presentation on Lafayette: Our Cancer Year at the second Comics and Medicine Conference in 2011. This project sent out a call for community stories from people who had been diagnosed with cancer. The submitted stories were then illustrated by local artists, and curated in an exhibit that featured Joyce Brabner speaking about her and Harvey Pekar’s graphic novel Our Cancer Year. The final Purdue comic was distributed back to the community where people could remember their loved ones, sacrifices, and the ways that the university, community artists, and patients could come together.

Inspired by Purdue’s project I wondered what this would look like as a teaching moment. I designed a two-quarter course that included having students collect illness narratives, work with a local artist, and draw a comic of their own based on the illness narrative. The goal of the course was to focus on relations and networks of people, objects, and spaces in regards to health and medicine. We considered what it means—to anthropologists and to the people with whom we work—to tell stories of people’s lives through text and imagery.

Inspired by Purdue’s project I wondered what this would look like as a teaching moment. I designed a two-quarter course that included having students collect illness narratives, work with a local artist, and draw a comic of their own based on the illness narrative. The goal of the course was to focus on relations and networks of people, objects, and spaces in regards to health and medicine. We considered what it means—to anthropologists and to the people with whom we work—to tell stories of people’s lives through text and imagery.

During the two quarters, 15 undergraduate students participated in the class. Working with a local community-based organization that served the needs of uninsured and underinsured women, or with the friends or relatives of some of the students, we each collected cancer narratives. Some of the topics the students and I discussed were the hope of living through a cancer diagnosis and most attended to specific events—receiving the diagnosis, treatment, or living past the death of a loved one.

The students then collaborated with a local artist to illustrate a moment in the narrative. Titled by the students as the “Letting Stories Inspire” project, these works of art were exhibited at the “Medical Examinations: Art, Story, Theory” conference that was sponsored by the Center for Ideas and Society. Community members who shared their stories with us, the students, and the artists attended the event. It was great to see these groups—who normally would not have connected—share their stories in a world that has increasingly become disconnected.

Another innovative use of comics in the community is the work of John Swogger. His comic Archaeology in the Caribbean was part of a public outreach project that included a daily comics journal describing the work that was being done at the site. Swogger’s blog details how the comics were installed in the Carriacou Island Tourism Office and distributed to local businesses and schools. Rather than leaving the community to wonder about the activities at the site and what the archaeologists might be doing with their history, John Swogger’s comics bridged the gaps between research and community.

Now, back to Fies’ Mom’s Cancer. This work has played an important role in building community and helping me find a new community. In the emerging field of graphic medicine, many scholars and comics artists often refer to his work as one of these moments when they were first intrigued and then inspired by the comic. During her Mayo Clinic “INSIGHTS” presentation, MK Czerwiec, aka Comic Nurse, discusses how she saw the cover of Mom’s Cancer across the room in a bookstore. It was an image that was familiar given her work as a nurse, but it was not something that is often seen in comics. Along with her own exploration in comics, this book enhanced the possibilities for comics as conveying the stories of community.

For me, Mom’s Cancer inspired a search that lead me to a new area of ethnographic comics scholarship, the creation of an innovative class that connected students with the community in which they live, a rethinking of methodologies and the need to incorporate imagery into our ethnography, and most importantly it connected me to the community of graphic medicine.