This is the second in a new series of blog postings by the Anthropology Teaching Forum (ATF) at the University of Texas, San Antonio. The first post introduced the ATF and its goal of building a strong teaching culture to match the research focus of the graduate program. This post offers a recap of a recent discussion on teaching philosophies—what they are, how they are defined, and how they inform different teaching styles—hosted by the ATF.

Teaching philosophies are ways to explore one’s own perspective on teaching and to communicate that perspective to students, hiring committees, and other educators. We discussed how to explore learning philosophies and general philosophical perspectives as personal context of your unique teaching philosophy.

One key introductory note is necessary before diving into the meat of our discussion. Over the course of our meeting, we found that a realistic distinction should be made between teaching philosophy as our main topic and teaching statements that make their way into job packets sent to hiring committees. The discussion here is most relevant to (idealistic, perhaps) teaching philosophy recognition and development. However faithful teaching statements are to teaching philosophies depends on the nature of the job, your teaching experience, and (rather cynically) your job desperation level. We acknowledge that teaching philosophies may be altered or padded to suit specific hiring opportunities but the focus here is on the teaching philosophy you carry around in your head more than anything you draft for a specific audience.

Leah discussed three key resources: Neil Haave (2014) on reflecting about your teaching philosophy, Maryellen Weimer (2014) on learning philosophies, and J.E. Beatty and colleagues (2009) on how general philosophy underpins teaching philosophies. Leah described Haave’s (2014) and Weimer’s (2014) emphasis on recognizing your learning philosophy as the foundation for your teaching philosophy. Learning philosophies are distinct from learning style (auditory, visual, etc.) and focus rather on motivations behind learning and the value you place on learning. Leah particularly emphasized a key facet of learning philosophies that struck her: how one deals with difficult learning experiences and those times when one may fail at understanding or mastering specific content. How does this affect how we approach learning? Further, how does this affect how we approach teaching? Leah discussed how she sees this particularly tied to a message in Haave (2014): instructor awareness and remembrance of what it is like to learn something brand new for the first time without the context developed over years of academic training and research. Leah suggested that this awareness of the students’ position (particularly in introductory courses) can and should relate to how instructors engage with student learning philosophies.

One point lacking in the discussion of exploring learning philosophy with teaching philosophy is the awareness of how instructor learning philosophies may mesh and/or oppose students’ learning philosophies. We discussed how direct experience with students and even institutional demographics (as a gauge before direct experience) may guide your understanding of student learning philosophies. It is important to stress that while the instructor’s awareness of their own learning philosophy is important as they engage in developing and/or revising their teaching philosophy, it is as important to be aware of student learning philosophies and the ways in which instructors and students compare/differ in how they are motivated to learn. One way that you can use learning philosophy to develop teaching philosophy is presented as a series of six interrelated questions in Haave (2014) to recognize exemplary personal learning and teaching experiences, how they connect, and how to provide such exemplary experiences for students.

One sub-topic in our discussion of teaching philosophies is the distinction of pedagogy and andragogy. Most of us are very familiar with the term pedagogy, referring to the methods and practice of teaching generally. If we were to do a search of teaching philosophy statements cross-disciplinarily, pedagogy might be top of the list of most frequently used terms. If taken literally and historically, pedagogy etymologically refers to teaching (or leading) children while andragogy refers to teaching (or leading) adults (Holmes and Abington-Cooper 2000). The age based distinction of child and adult while relevant for primary or secondary education, may not be the most relevant approach for a higher learning context. It may be more effective to think about the distinction of general novices (e.g. children) and general experienced (e.g. adults who are not novices in terms of life experience but may be novices in terms of course content).

In terms of how this may affect your teaching philosophy, it is interesting to reflect on how you perceive your students. Do you see the students who populate your classroom as general novices that need controlled and dictated leadership? Do you see your students as experienced, with skills that make them equipped to develop the specific knowledge base relevant to your class via their own constructions and ownership? We discussed how this dichotomy is useful and how it is overly simple. We recognized the need for a blended approach, specifically in courses with heavy factual content loads, such as biological anthropology (i.e. fossil record and human evolutionary trends). Overall, the recognition of how you as an instructor view your students is important for developing a relevant and authentic teaching philosophy.

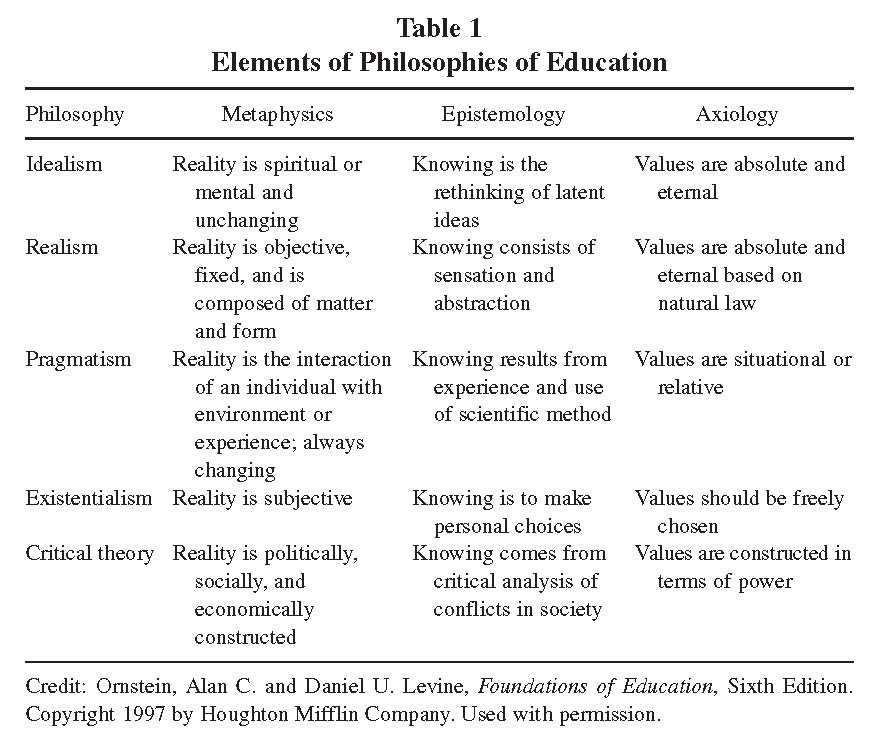

The bulk of our discussion centered on Beatty and colleagues’ (2009) novel approach to contextualizing teaching philosophies. The authors suggest grounding teaching philosophies in general philosophical perspectives. They describe five general philosophical perspectives (idealism, realism, pragmatism, existentialism, and critical theory) via three criteria: metaphysics (what is real?), epistemology (how do I know what I know?), and axiology (what is the basis of my judgment and ethics?). The chart (Beatty et al 2009: 107) below summaries these perspectives well:

Beatty et al (2009) describe how each general philosophical perspective may impact teaching philosophy. We discussed where we personally see ourselves falling in this classification and how these personal perspectives affect how we teach. For example, Leah confessed her general alignment with the existentialist emphasis on subjectivity and the importance of personal choice. This is reflected in her clear focus on student choice in the classroom via focused archaeological research projects, seminar assessment, and choice-driven activities such as mock excavations. Beatty et al (2009: 109) state that instructors with an existentialist perspective are more likely to emphasize experiential learning in their classrooms. It is not difficult to trace Leah’s keen devotion to experiential learning through previous posts and recaps for the ATF! Dr. Mary Kelaita (Post-Doctoral Fellow in the UTSA Department of Anthropology) described her personal connection to relating unknowns (course content) to knowns (from personal experience) during her undergraduate career. Through awareness of her pragmatist perspective, she guides her students to make similar personal connections with content in biological anthropology courses. All participants acknowledged that while this classification is insightful, it does not follow that we are beholden to only one perspective. We can be a blend of two or several. The recognition and awareness of wherever we do fall is what can impact or improve your teaching philosophy.

Beatty et al (2009) describe how each general philosophical perspective may impact teaching philosophy. We discussed where we personally see ourselves falling in this classification and how these personal perspectives affect how we teach. For example, Leah confessed her general alignment with the existentialist emphasis on subjectivity and the importance of personal choice. This is reflected in her clear focus on student choice in the classroom via focused archaeological research projects, seminar assessment, and choice-driven activities such as mock excavations. Beatty et al (2009: 109) state that instructors with an existentialist perspective are more likely to emphasize experiential learning in their classrooms. It is not difficult to trace Leah’s keen devotion to experiential learning through previous posts and recaps for the ATF! Dr. Mary Kelaita (Post-Doctoral Fellow in the UTSA Department of Anthropology) described her personal connection to relating unknowns (course content) to knowns (from personal experience) during her undergraduate career. Through awareness of her pragmatist perspective, she guides her students to make similar personal connections with content in biological anthropology courses. All participants acknowledged that while this classification is insightful, it does not follow that we are beholden to only one perspective. We can be a blend of two or several. The recognition and awareness of wherever we do fall is what can impact or improve your teaching philosophy.

We discussed the practicalities of what this philosophical approach to teaching philosophies means for how you present your teaching philosophy to others. Is it necessary to spend time in already savage page limits or word counts to expound on why you lean existentialist or towards critical theory? Probably not. But reflecting on these philosophical perspectives can be significant to contextualizing your unique philosophy of teaching and why you are motivated to teach the way you do. Teaching statements can reflect these general perspectives and provide insight into you as an individual.

To conclude the meeting, Leah emphasized the PROCESS of reflection for teaching philosophies. While the practicalities of writing teaching statements are important, formalizing your teaching philosophy for yourself and thinking about how, ideally, you want to teach can be an opportunity to directly improve and connect back to the classroom. Particularly, Leah emphasized reflection on how your teaching philosophy (inclusive of your learning philosophy and general philosophical perspective) relates to/engages with/ignores your students’ learning philosophies. It may be a good exercise to recognize learning philosophies evident among your students and how your teaching philosophy plays to their strengths, challenges them to try new things, or flies straight over them. Further, we recognized that students being exposed to a diversity of teaching philosophies (via different professors, disciplines, and year levels) is likely a very good thing for the development of critical thinkers and general life skills.

All participants expressed interest in this topic and these novel ways of attacking teaching philosophies. In the future, ATF hopes to organize an update or extension to this session to directly discuss the construction and finagling of teaching statements.

Leah McCurdy can be reached directly at leah.mccurdy@mavs.uta.edu.

References:

Beatty, J.E., J.S.A. Leigh, and K.L. Dean. 2009. Philosophy Rediscovered: Exploring the Connections Between Teaching Philosophies, Educational Philosophies, and Philosophy. Journal of Management Education 33(1): 99-114. https://jme.sagepub.com/content/33/1/99.abstract

Haave, Neil. 2014. Six Questions That Will Bring Your Teaching Philosophy into Focus. Faculty Focus https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/philosophy-of-teaching/six-questions-will-bring-teaching-philosophy-focus/

Holmes, Geraldine and Michele Abington-Cooper. 2000. Pedagogy vs. Andragogy: A False Dichotomy? The Journal of Technology Studies 26 (2). https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JOTS/Summer-Fall-2000/holmes.html

Weimer, Maryellen. 2014. What’s Your Learning Philosophy? Faculty Focus

https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/whats-learning-philosophy/