Bob Muckle teaches at Capilano University in British Columbia. Researching, teaching, and writing about Indigenous peoples in North America is one of his specialties. Recent books include Indigenous Peoples of North America, Introducing Archaeology, Second Edition, and Through the Lens of Anthropology (co-authored with Laura T. Gonzalez).

Teaching about other peoples and cultures is often challenging. For me this includes teaching courses on Indigenous peoples and cultures of North America, including those known as Native Americans, Indians, Aboriginals, and First Nations.

I am an anthropologist in a position of privilege, teaching about, and often to, people who have been, and continue to be, exploited by the dominant society, of which I am a part. I struggle with this. Always have. The struggle is based in part on a lack of authenticity in conveying the emic (or insider’s) view of the cultures, and difficulties of teaching about a sense of place. Maybe “authenticity” isn’t the correct word here, but what I mean is that since I am not Indigenous, some students may not consider me to be an authentic conveyor of Indigenous culture. Given the long, problematic history between anthropology and Indigenous peoples I am wary of wanting, or even being able, to be an expert or offer an insider’s perspective. I usually address the lack of authenticity in the first minutes of the course, letting students know that this is an anthropology course, I am an anthropologist, and I have many years’ experience working with and for First Nations. I then try to provide the emic perspective in other ways. I make it clear that I make no pretext of having an insider’s perspective (although I can certainly describe the experiences of myself and others), and also explain that being an anthropology course, the focus is on anthropological rather than Indigenous perspectives (meaning, for example, that students are learning about how anthropologists study Indigenous peoples, such as the through archaeology and the comparative approach). I also give considerable voice to the Indigenous students in my classes, and have guest lectures by Indigenous peoples on campus.

I am an anthropologist in a position of privilege, teaching about, and often to, people who have been, and continue to be, exploited by the dominant society, of which I am a part. I struggle with this. Always have. The struggle is based in part on a lack of authenticity in conveying the emic (or insider’s) view of the cultures, and difficulties of teaching about a sense of place. Maybe “authenticity” isn’t the correct word here, but what I mean is that since I am not Indigenous, some students may not consider me to be an authentic conveyor of Indigenous culture. Given the long, problematic history between anthropology and Indigenous peoples I am wary of wanting, or even being able, to be an expert or offer an insider’s perspective. I usually address the lack of authenticity in the first minutes of the course, letting students know that this is an anthropology course, I am an anthropologist, and I have many years’ experience working with and for First Nations. I then try to provide the emic perspective in other ways. I make it clear that I make no pretext of having an insider’s perspective (although I can certainly describe the experiences of myself and others), and also explain that being an anthropology course, the focus is on anthropological rather than Indigenous perspectives (meaning, for example, that students are learning about how anthropologists study Indigenous peoples, such as the through archaeology and the comparative approach). I also give considerable voice to the Indigenous students in my classes, and have guest lectures by Indigenous peoples on campus.

Addressing the sense of place has been more challenging. I find teaching about a sense of place among Indigenous peoples and cultures difficult to do in a regularly scheduled course in a regularly structured term in a standard university building in an urban area. I find it difficult to teach about a sense of place without being in those places. Reading about it, talking about it, showing pictures somehow isn’t enough. I’ve always wished for students to be better able understand an Indigenous sense of place.

With these two challenges (authenticity and place) in mind, I recently created a new course on Indigenous Peoples and taught it in a condensed seven-week term. The class met every Friday from 9:00 – 4:00 and focused on the First Nations of the Greater Vancouver area. Four days were spent off-campus and three were spent on-campus. During the on-campus days, students received core content such as current profiles of the more than a dozen First Nations in the region, and lectures on the anthropological perspective, local archaeology and ethnography, and the impacts of colonialism. The primary focus was on three First Nations—the Musqueam, Tsleil Waututh, and Squamish—whose traditional territories include where most students live and go to university.

Having the course scheduled for one entire day each week was key, providing the opportunity to go off-campus for several hours without students needing to accommodate other courses or work. The class had 30 students and there was a $70 surcharge to cover expenses.

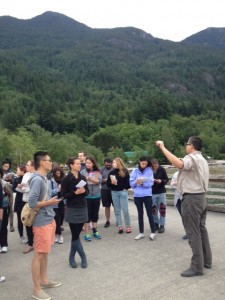

Field trips were designed for students to experience and learn from First Nation educators in their own territories, providing both some authenticity to the information and a sense of place. This included being on reserves and in environments with important cultural and spiritual significance. Places we visited included a Musqueam reserve, Cates Park (a popular recreation and beach area in Tsleil Waututh territory), several locations within Squamish Nation territory, and Stanley Park (a large urban park with interests shared between the three nations). In each case, a member of the relevant First Nation guided the class.

Students were evaluated on four 1,500-2,000 word field reports, which included a thorough description and discussion of each trip. Writing descriptions was designed to introduce students to anthropological fieldwork, making good observations, and detailed notes. Discussions were included to demonstrate students’ ability to link their observations with lectures, readings, and other field trips.

When organizing the field studies, the First Nations educators were given no restrictions in what they wanted to talk about or do. They knew that this was a university anthropology class focusing on the local First Nations, and would be including visits to other nations’ territories as well. Common themes that were addressed by each of the First Nations educators included the importance of language (each spoke some, and two sang), place names, archaeological sites, traditional ecological knowledge, the importance of family, relationships between groups, relationships between places and culture, and cultural activities in contemporary times.

I judge the course to have been enormously successful. Student feedback was positive. For me, it was a very effective way of dealing with the challenges of authenticity and teaching about place. Based on their field reports, students learned a great deal about the lens of anthropology and First Nations.

Many students commented on how interesting it was to learn not only about Indigenous perspectives on places and peoples, but how different some of the Indigenous perspectives were from each other. I was hoping this would happen. I not only wanted the students to appreciate differences between First Nations’ and anthropological perspectives, but that not all First Nations peoples had a consensus view. Students also commented on how little conflict they found between First Nations’ and anthropological perspectives.

An added benefit of the course is that it hits upon some of the themes my (and other) universities are pushing these days, including experiential learning, indigenizing the curriculum, and indigenizing the academy. Having four First Nations educators involved in the course doesn’t quite qualify as indigenizing the academy as much as I would like, but it is a step in the right direction.