Graphic Adventures in Anthropology

This is the third post in a new blog series called Graphic Adventures in Anthropology. Once a week for 7 weeks, a guest contributor will write about some aspect of graphic anthropology (and by “graphic” we mean drawing in general, and comics in particular), from visual culture to visual communication, and from ethnographic method to dissemination device, culminating in the announcement of a new series we are launching at the press called ethnoGRAPHIC. Here’s the line-up:

Andrew Causey: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method

Stacy Leigh Pigg: Learning Graphic Novels from an Artist’s Perspective

Sherine Hamdy & Mona Damluji: Reflecting on Arab Comics: 90 Years of Visual Culture

Coleman Nye: Teaching Comics in a Medical Anthropology & Humanities Class

Gillian Crowther: Fieldwork Cartoons Revisited

Juliet McMullin: Comics in the Community

Nick Sousanis: Unflattening Scholarship with Comics

Anne Brackenbury: ethnoGRAPHIC: A New Series by University of Toronto Press

See last week’s blog posting here.

Learning Graphic Novels from an Artist’s Perspective

By Stacy Leigh Pigg, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Simon Fraser University

About five years ago, I was hit by a bolt of lightning. It happened on an otherwise normal workday, while I was struggling to tame what was becoming an increasingly unwieldy project. In a single bright flash, I pictured the entirety of my project in the form of a graphic novel. Establishing shots that parachute the reader into a specific place. Close-ups that bring the reader into the mind of a person. Simplifications that focus attention. Relationships among people inscribed in gestures, pose, action. Panels whose very internal composition and arrangement on a page move the reader through multiple perspectives. Pages whose layout make an implicit argument about how one thing is connected to another. In my mind’s eye, the exaggerated staging of sequential snapshots could lift my story out of the sticky slowness of explanation.

Later I learned that theorists of comics have a lot to say about this: how to compose images so that they propel a story and how to combine word and image in a single effect. Graphic novels are neither an illustrated text nor drawing with captions. They can be considered a third medium with unique possibilities.

Later I learned that theorists of comics have a lot to say about this: how to compose images so that they propel a story and how to combine word and image in a single effect. Graphic novels are neither an illustrated text nor drawing with captions. They can be considered a third medium with unique possibilities.

But how to get from my eureka to a real product? Recently I stopped speculating and enrolled in a course on contemporary comics at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design. In the course, we would follow the steps to draw a few pages of our own comic. Problem was, the last time I had actually drawn anything was . . . um . . . maybe 1973?

Let me walk you through my experience in the course, week by week.

Week 1: Come up with a story idea

Feeling brave, I decide to use the course to start converting an existing ethnographic essay into the graphic format. I choose a famously vivid action scene written by the inventor of “thick description” himself. After all, it was already scripted.

Week 2: Life drawing

I’m apprehensive. This will be the first time I make lines on paper, and my task is to draw a live model in the buff? Really? Entering the classroom with my newly purchased pad of newsprint and the mysterious tool called conte crayon, I feel like a proud 6-year-old on the first day of school. Or maybe like Malinowski on the island beach, as the boat recedes over the horizon.

Positioning myself astride the drawing stool, clipping my paper pad to the drawing board, I repeat ArtSchoolDaughter’s parting tips. “Find the action line.” “Draw the negative space.” The first poses are held for a mere 30 seconds, most of which I spend fumbling with my tools. As the poses get longer, I’m hyper aware of myself trying to look, working to think in shapes, understanding space, light, and shadow as solid things, something my fellows with art training already do fluidly. I may not be able to do it myself, but I can intellectualize it: it’s embodied knowledge. As the model holds his body in an interesting shape, our arms and hands dance in arcs and strokes in response. The only sound in the room is the susurration of conte crayon on paper. I’m getting it. I’m supposed to understand the relationship between parts and wholes. Riding home on the bus, fellow passengers look like action lines and negative space.

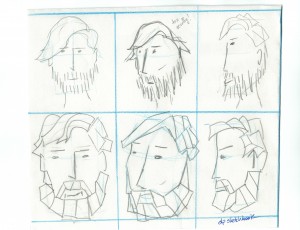

Week 3: Homework: “Create 3-5 pages of rough character sketches”

In time-honored tradition I wait until the night before class, only to discover I am in way over my head. Clutching a 2B pencil, my hand hovers over the seemingly infinite white expanse of my pristine sketchbook. I have no idea how to tackle drawing a face (let alone a whole body, or the head and body seen from four different angles). And who is my “character”? The anthropologist who wrote the essay, or the people whose actions he analyzes?

The internet gives me a handful of publicity photos of the anthropologist, taken decades after the ethnographic moment I have chosen to depict. ArtSchoolDaughter says: “Start with the shape of the head. Then choose one distinctive feature of the face to emphasize as the mark of that character.” She shows me 10 different ways to draw Famous Anthropologist’s beard. My other “characters” are described in his writing only as a generic collective (“the Balinese”) or as a social role (“the village headman”). Feeling like a 19th-century phyiognomist in search of racial types, I comb through unendingly repetitive tourist photos on the internet to give me faces I can copy.

Riding home on the bus after the class critique of my sketches, I decide that Famous Anthropologist would not have had a beard in 1959. Instead he wore glasses.

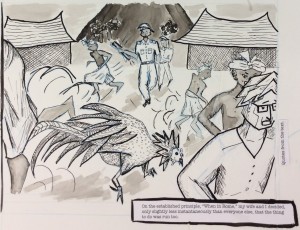

Week 4: Create preliminary thumbnail sketches depicting scenes in your story

I find it strangely hard to commit to lines. To commit a line. When I write I certainly expect to draft, to cross things out, to start over, to move sections around, to rewrite. Now, neither my big eraser nor an unlimited stack of cheap paper reassures me. My teacher has demonstrated sketching rough and fast with blue pencil, circling a shape until you “find the line.” He has shown us how to conceptualize a body in 3D by seeing it as a stack of blocks.

Still, I am hyper aware that every mark externalizes a decision. The roofs of the houses look like this. The men tie their turbans thusly. A woman would carry this item, and yes, her breasts would be bare. The expression on her face should be so. Whether or not a comic artist intends a realist aesthetic, or a high level of detail, the drawing must pull the reader into a plausible, imaginable world. The utter persuasiveness of the visual smacks me in the face. (“Duh.” ArtSchoolDaughter rolls her eyes.)

“Can one overthink the politics of representation in comics?” I ask myself. No, I decide. Not in the ethnographic graphic. Not after anthropology’s reflexive turn, not after the critique of naïve objectivism and ethnographic authority, and not as we try to decolonize anthropological knowledge production. And we already know that there will never be one single obvious, correct way to handle representational decisions. Understanding those choices, and inventing new representational solutions, is part and parcel of anthropological practice.

Note to self: Research, including archival research, will be necessary. (ArtSchool daughter says “everyone uses reference photos.”) Second note to self: Aesthetic interest in realism and accuracy does not resolve representational quandaries. Deciding what to leave out matters as much as deciding what to put in.

That’s what is interesting. The possibilities keep me entertained on the bus.