To mark the publication of Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method, author Andrew Causey provides the following thoughts on how drawing can also be used in the classroom to teach students about seeing and perception. Drawn to See will be launched this week at the meetings of the American Anthropological Association in Minneapolis. To see how attendees at the conference apply advice from the book, follow #sketchAAA on Twitter.

To mark the publication of Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method, author Andrew Causey provides the following thoughts on how drawing can also be used in the classroom to teach students about seeing and perception. Drawn to See will be launched this week at the meetings of the American Anthropological Association in Minneapolis. To see how attendees at the conference apply advice from the book, follow #sketchAAA on Twitter.

When I was a kid, we played a game called “Hot Potato” in which a beanbag was quickly passed from hand to hand until the leader called out “HOT!” Whoever was left holding the limp bag was ejected from the game… and so, around and around it went until only one person was left.

I am reminded of that old game each time I teach my Visual Anthropology course and share ethnographic objects with my students. It doesn’t matter if I have a Dani woven belt from Papua Province, Indonesia, carefully decorated with yellow orchid stems and cowry shells, or if I have an intricate huipil from the Mayas of Guatemala. It doesn’t matter if I hand a Javanese kris handle to the person on my left, or a Tohono O’odham coil basket from southern Arizona to the person on my right, the reaction is almost always the same: the object flies from hand to hand and ends up in front of me on the desk in mere moments. Even if I wanted to, I’d have no time to shout “HOT!”

At first, I was stunned that students at an arts college would seem to take so little interest in objects from cultures so distant from theirs. I suppose I assumed that students who gravitated to studying film, dance, creative writing, interactive multi-media, and sound engineering would naturally be drawn to the world of global aesthetics. I began to get a little depressed thinking I had so misread my students and their interests. But after a few years of disappointment, I began to realize something important: students were not disinterested in the objects I handed them, they passed them on because they were “done;” the fleeting experience had satisfied their curiosity. In essence, they could hold them, but they were unable to see them.

What I mean is this: my students (like many of us in fast-paced western societies) are so busy scanning the world that they may have lost their knack for actually perceiving objects and images carefully and mindfully. We all seem to be looking… but not seeing.

What I mean is this: my students (like many of us in fast-paced western societies) are so busy scanning the world that they may have lost their knack for actually perceiving objects and images carefully and mindfully. We all seem to be looking… but not seeing.

This should not come as a surprise. Many of us live in an increasingly complex visual world that requires us to view, read, interpret, and understand thousands of images a day, from 3-dimensional objects in our homes, schools, and jobs, to 2-dimensional pictures in newspapers, magazines, and on billboards, to digital depictions shown to us virtually on the internet and within our social media platforms. To make sense of this jittering and jostling passel of images—all of which are vigorously struggling for our attention—we end up glancing at, and reacting to, surfaces, while missing deep content and context.

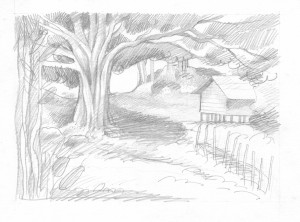

My book, Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method, addresses this situation head on. While doing ethnographic research with the Toba Batak people of North Sumatra, Indonesia I slowly realized that some understandings of life on Samosir Island became clearer to me when I began to draw what I saw rather than simply write about it. I later brought this realization to the classroom. Using techniques I adapted or developed over eight years of teaching my course, in Drawn to See I show readers how to enhance their abilities to improve their ethnographic seeing by means of line drawing. The focus here is not “learning how to draw.” Rather, my intent is to show students of ethnography how to use drawing as a pathway to more attentive perception.

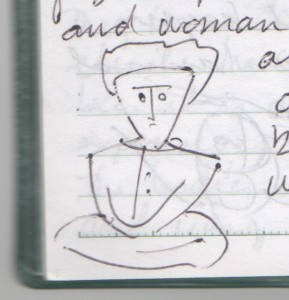

Starting with the assumption that many readers come to the book with a firm conviction that they can’t draw, I begin to dismantle this harmful (and false) notion, replacing it with a more fruitful concept: drawing is not a product, it is a process. By means of practical suggestions and calm encouragement, I lead the student to a place where negative judgment is banished and where exploration and play are promoted. Using a series of 39 calibrated drawing exercises interspersed with real-life ethnographic examples of how drawing can enhance anthropological investigations, I show how line-work can work together with word-work to convey a richer and more multi-dimensional perspective on understanding and appreciating varied cultural worlds.

Starting with the assumption that many readers come to the book with a firm conviction that they can’t draw, I begin to dismantle this harmful (and false) notion, replacing it with a more fruitful concept: drawing is not a product, it is a process. By means of practical suggestions and calm encouragement, I lead the student to a place where negative judgment is banished and where exploration and play are promoted. Using a series of 39 calibrated drawing exercises interspersed with real-life ethnographic examples of how drawing can enhance anthropological investigations, I show how line-work can work together with word-work to convey a richer and more multi-dimensional perspective on understanding and appreciating varied cultural worlds.

Instructors who use the book should not feel intimidated by their own feelings of drawing insecurity. I have endeavored to let the book be the guide to this method, not requiring any special background or knowledge to open the door to drawing as a way of seeing.

My most compelling evidence that this method works in the anthropology classroom is that each semester my students evince a more developed curiosity and begin to more thoroughly appreciate and deeply perceive the world around them as the weeks unfold. Not only that, but when I bring objects to share in the classroom at the midpoint of the course, it doesn’t look like each student is trying to get rid of the object before I yell “HOT!”