I have had the privilege of being taught by some amazing, thoughtful, and supportive people during my undergraduate and graduate training at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Dr. Jill Fleuriet is one of those inspirational teachers, so when I matriculated into the MA program in the spring of 2011 and saw she would be running the Teaching Anthropology seminar, I jumped at the opportunity to learn about teaching from her. Since that first semester of grad school, I’ve had many teaching opportunities in the Department of Anthropology both as a TA and as an instructor of record. One important factor in my preparedness for those roles was Dr. Fleuriet’s class. Three years out, I’m happy to take this opportunity to reflect on how Dr. Fleuriet’s Teaching Anthropology course has played an integral part in my development as a teacher.

As a first-semester grad student, at times I felt utterly unprepared and unqualified for the seminar. Many of my peers had worked as TAs or taught their own courses, and this was the first time I had even thought in any meaningful way about the practice of teaching. In some ways, my complete lack of teaching experience was beneficial; I was able to think clearly about what sorts of things I enjoyed or hated as an undergraduate as those experiences were still fresh in my mind. But in other ways, my lack of teaching experience made it difficult to adequately complete some of the exercises. For example, one of the first exercises was to draft a teaching philosophy statement. I found this exceptionally difficult because I had never thought about myself as a teacher, and I certainly had not read much about pedagogy. As difficult as that exercise was, it did help orient my thinking toward the practice of teaching and brought my attention to the level of intentionality required for teaching well.

Looking back over the last few years, I now see quite clearly how important experience is to developing one’s self as a teacher. During Dr. Fleuriet’s seminar, I was never short on ideas, and I enjoyed spending time imagining various ways I might construct and run a course. But it wasn’t until I started teaching my own courses that I could determine whether the ideas I devised for student activities and assignments were any good. I also discovered that what works for one course may not work in other courses, or even in different sections of the same course. Classroom dynamics, student personalities, and how interesting the topics are (both to students and to myself) all play into what works and what bombs. Some of the ideas I came up with in Dr. Fleuriet’s course looked great in theory, but in practice turned out to not work so well. This was something we discussed with regularity in the seminar, and since we had the space to talk about it in the course, I expected many of my ideas to fail in practice. Still, I was not afraid to try things out because I felt equipped to salvage or alter the course in the face of teaching failures.

I also learned how important it is to view each course as unique and to treat it dynamically rather than as a static thing that will always work the same way. Dr. Fleuriet’s class taught me the importance of regularly evaluating my own performance, being open to constructive criticism and feedback from students on how to improve the course (both the current course and future courses), making sure students actually know that I am always open to such feedback, and most importantly structuring my courses so they are flexible enough to respond to the needs of current students. Continuous reflexive peer reviewing (something we practiced in Dr. Fleuriet’s course) taught me to distance myself from my ideas so I can be critical enough to alter or abandon things that don’t work, as well as to keep improving the things that do work.

An example of how this has played out in my own teaching is one of the assignments I have incorporated into my upper-division courses: daily critical discussion questions. Students are expected to demonstrate their reading comprehension and ability to synthesize course material by constructing their own critical questions about the readings with the goal of posing questions that will direct in-class discussion. When I first began using this assignment, most of the questions students were submitting were not meeting my expectations, despite being given detailed instructions and feedback. Because I had left myself some wiggle room in my course schedule, I set aside a full 50-minute class period to talk about the assignment and my expectations with the class in more detail. After explicitly detailing what I meant by critical thinking and by higher-order thinking (i.e., the top half of Bloom’s Taxonomy), I had students talk through how some example questions could be improved to incorporate higher-order thinking. Taking the time to do this with the students was exactly what was needed, and the quality of questions improved immediately. By the end of the semester, the vast majority of the students in the class were writing some of the most critical, insightful, and thoughtful questions about the readings simply because we took the time to explore together what “synthesis” and “evaluation” look like.

I share this example because I think Dr. Fleuriet’s class primed me to view teaching as a dynamic relationship with students as well as an ongoing process of critical self-evaluation, and those values were what allowed me to turn a good assignment with poor responses into a great assignment with fantastic responses. I am currently using the discussion question assignment in another different upper-division class, and the students are going through a similar pattern, rapidly improving the quality of their questions after our in-class discussion about how to practice higher order thinking. I am also more intentionally modeling synthesis and evaluation in each class, and reminding students to work on using these skills when reading and constructing their questions.

One final benefit of Dr. Fleuriet’s course: I began to lose my fear of speaking in front of groups. In addition to regularly sharing and discussing materials with peers, we had to prepare and deliver a lecture on a topic outside of our subdiscipline, which was recorded and uploaded to the course website where all of our peers could see it. This was the first time I had to do lecture prep, which was an eye-opening experience. It was also the first time I would have to deliver a 50-minute lecture.

While delivering the lecture to an empty classroom and a camera person remotely controlling the recording equipment is not at all like delivering a lecture to a room of 80 undergraduates, the fact that I had to get up in front of a stranger and deliver a lecture on a topic outside of my specialty—and knowing that all of my classmates would see it—was nerve-racking to say the least. I powered through it and was quite proud of what I accomplished. I found myself exhilarated afterwards and excited by the idea that I could someday be in a position to do such a thing on a regular basis.

The other exercise that helped me overcome my fear of public speaking was when Dr. Fleuriet sent our class out into the commons area during the busy lunch time, divided us in half, made us stand on benches on opposite sides of the courtyard, and read monologues from Monty Python to each other. Having to stand up high where everyone within earshot can see you, and read something loud enough to project your voice to the group 20 yards away over the hustle and bustle of lunch time on a college campus was terrifying at first. But we all did it, and we all ended up having fun in the process.

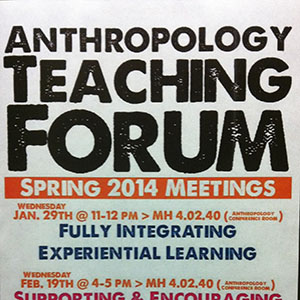

I am grateful to have been able to work in a department with so many wonderful colleagues and peers who care about teaching. In fact, a few of the grad students and faculty got together and started the Anthropology Teaching Forum last spring as a way for those of us who are interested in teaching anthropology to continue collaborating and improving our teaching skills. The ATF has allowed us to go into depth on various topics and ideas that some of us discussed while taking Teaching Anthropology, and it has allowed us to tap into each other’s knowledge in useful and transformative ways.

Dr. Fleuriet’s Teaching Anthropology class is a manifestation of a departmental culture that values teaching as an important aspect of scholarship. There is so much more I could write about how the seminar specifically helped prepare me to teach. Suffice it to say, I am leaving UTSA to begin a doctoral program with more teaching experience than many people at my career stage have, which undoubtedly strengthened my PhD applications. If I had not had the opportunity to take Dr. Fleuriet’s course, I would have struggled much more while constructing and implementing my own courses. I would advocate for all graduate-level programs to implement similar courses that incorporate a discipline-specific focus into pedagogical and practical teaching training in the spirit of encouraging and guiding junior scholars in ways that will create positive teaching environments in the academy.

Will Robertson is a medical anthropology PhD student at the University of Arizona. His research focuses on queer health disparities and medical education and practice. You can find him on Twitter @anthrowill.