With #inktober now in its 10th year, Katherine Cook explains the on-going success of the campaign, and discusses the evolution of #archink.

As instructors, we often have rather lofty aspirations when we set assignments for our students, hoping for innovative approaches, clever problem-solving, effective communication. At the core of these values is creativity, and yet we rarely actually teach creativity as a skill to be valued in academic anthropology.

A couple of years ago, while teaching digital archaeology, I was finding that students were very capable of applying their newly developed skills in coding and platform design (see Coding Culture blog series), but often only to replicate the models for application that they had seen, rather than imagine novel uses of the technology. And so began a series of creative interventions in my classrooms.

This has at times included paper prototyping of digital applications (such as maps or games), dramatic reenactments, and invention competitions. However, #inktober has by far been one of the most lasting, because it brings together an out-of-the-box activity with a structure intended to build a lasting habit.

What is #Inktober?

Inktober was first created in 2009 by an artist looking to challenge their own skills and develop drawing habits. It eventually grew to an annual, worldwide challenge for professional artists and beginners, and everyone in between. The structure is simple: 31 days, 1 drawing per day (and post it online if you choose with #inktober). In practice, it has been a bit more varied, with some choosing to do a drawing every other day or every week – it is about habit, not torture!

Each year, an official list of prompts is circulated – typically a list of 31 relatively random words (often a bit eerie to fit the month of October). In recent years, spinoff prompt lists have emerged for specialized groups, such as an architecture list, and associated spinoff hashtags.

How does #Inktober fit into a classroom?

To incorporate this into class as a take-home assignment, I started making prompt lists that related to the subject matter (typically archaeological or heritage in nature), though students had the option of going off brief. The prompt list helps to trigger ideas each day, particularly important for later in the month when ideas start to dwindle! They also force students to think about concepts relevant to learning outcomes and find a way to communicate it visually, which contrasts sharply with how they might describe it in an essay or exam.

Grading student Inktobers varied from course to course, depending on the structure and role of the exercise; in some instances, it was treated as a bonus exercise with a small amount of extra marks given for completion, whereas in other courses, focused on communication in archaeology, formal grades were given for the creative but also accurate depiction of concepts. Effort to experiment, innovate, and take risks were also taken into consideration.

There are many more options for implementing this in your own classrooms to play with visual note taking styles to help students engage with course content and communication. You could, for instance, use an Inktober-style exercise as a regular revision technique at the beginning or end of each lecture for 3-5 minutes of sketching and potentially small group sharing and discussion. It doesn’t even have to be October! Other modifications are also possible; if you don’t want to have students share through social media, use online course discussion boards instead.

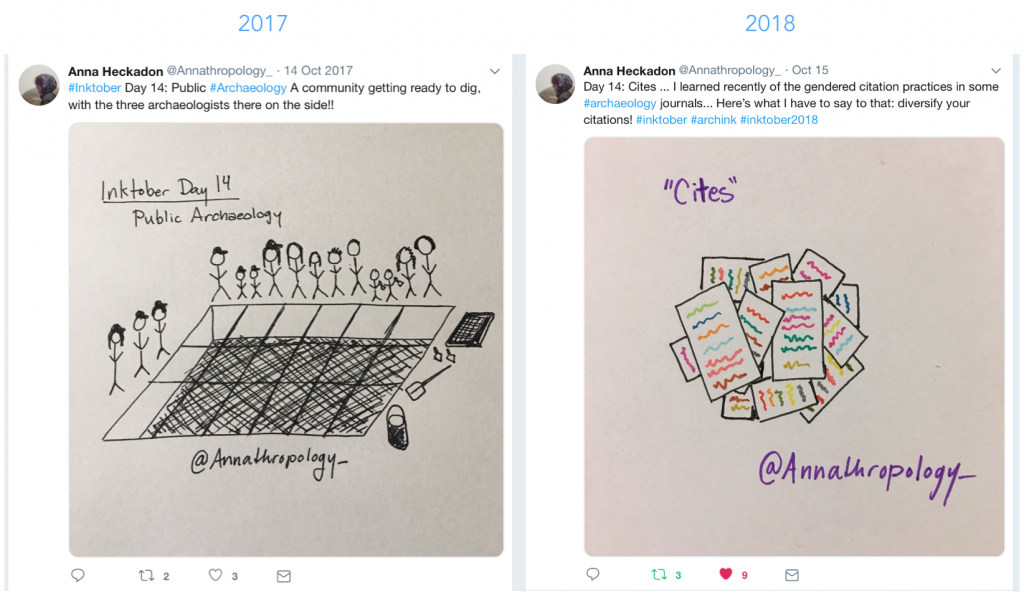

An example of undergraduate student inktobering, from 2017 and 2018 (with permission of Anna Heckadon)

Why #Inktober?

To be completely honest, I almost forgot about Inktober this fall as I am not teaching my usual courses, however former students asked if I would provide prompts again, and when students ask for extra homework for a course that has already been completed, it has clearly had an impact!

This year, since it is largely taking place via social media (Instagram, Twitter) through the hashtag #archink, instead of a closed classroom, a much wider community of archaeologists has jumped on to the Inktober bandwagon, with a faithful following in the Twitter/Insta-sphere. For many of us, including higher education instructors and professionals, it has been a great way to learn new tricks and think through our own research and practice.

So what does #inktober and #archink contribute?

1) Creativity is a skill, and one that needs to be practiced and exercised regularly. Engaging in a small act of creativity every day builds habit. Even if your daily inking dwindles after the month, it is a muscle that will be more easily tapped into in future.

Inktober by Beth Compton, PhD student, communicating the complexity of replication, linked to Magritte, visual theory and representation.

2) At its core, Inktober is really about creative forms of communication. The ways in which we represent the world around us (including our discipline), frame and compose it visually, re-envisioning scientific communication. Particularly with the importance placed on #scicomm and community engagement today, creative communication is a skill in high demand.

3) Critical thinking doesn’t need to be essays or debates. Creative communication requires many of the same analytical and evaluative skills, as well as problem solving and originality, that we expect from traditional assignments in higher education (and research more broadly), but it can be a lot more engaging and motivating. It doesn’t matter what your artistic skill level is either, even stick figures can communicate extremely complex ideas about anthropology.

4) Although I would argue that the social sharing of drawings is not critical, it does build a community of practice. The value that has emerged particularly this year has been the sharing of images by individuals at different stages of education and career, in different countries and from different specializations. Each prompt, therefore, results in vastly different interpretations perspectives. Styles, composition, and media have also varied. Fellow Inktoberers then learn from each other, get to know each other, and engage with wider communities through conversations stimulated by the content.

5) With each passing day, there is a growing body of creative anthropological visuals, many of which are being shared with Creative Commons licenses so that they can be used in teaching. It is often difficult to find open access and CC licensed images in anthropology, particularly ones that communicate complex theory, concepts, and applications, so this will certainly be a great resource moving forward.

As I write this, Inktober is sadly coming to a close for another year. However, it is not too late to follow #archink, to join in or to bring this practice to your own classrooms, and if possible, share the results with the creative anthropology community!

Katherine Cook is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Montreal, Canada. As an archaeologist/anthropologist/historian, her research brings together collaborative, digital and public practice to examine the construction of family, race, and religion in Canada, the Caribbean and Europe. Follow @KatherineRCook on Twitter for more adventures in teaching and doing digital/public anthropology.