In the first of a two-part blog post, Marie-Eve Carrier-Moisan talks about the challenges of adapting her ethnographic work on sex tourism in Brazil into graphic novel form. Gringo Love: Stories of Sex Tourism in Brazil will be available in 2019 from the University of Toronto Press.

By Marie-Eve Carrier-Moisan

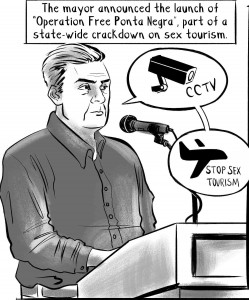

Comics and graphic novels present unique modalities, potentialities, and challenges for anthropological knowledge production – something that I had become acutely aware of as I work my way through the making of my first graphic novel, Gringo Love: Stories of Sex Tourism in Brazil. The project is an ethno-graphic collaborative experiment that draws on ethnographic research and that focuses on a group of Brazilian women as they negotiate different encounters with foreign men, or gringos, in the city of Natal. These women tell stories of their hopes, struggles, pains, and pleasures, but mainly they talk about their desire to “escape their lives”, not their lives in sex tourism, as one may assume, but their lives in Brazil where they experience various forms of oppression. The graphic novel also situates Eva, the anthropologist, as part of the story. As narrator, Eva presents women’ experiences against the backdrop of various misguided interventions to either rescue them or erase them from public visibility.

The collaboration has included the participation of Dr. William Flynn who is helping with the visual conceptualization – that is, the translation and adaptation of written research work into a storyboarded version – and Débora Santos a Brazilian graphic artist who is illustrating the work (I have very limited drawing abilities!). The graphic novel is still in the making. It has been partially funded by a SSHRC Insight Development Grant and under advance contract with the University of Toronto Press, as part of its EthnoGRAPHIC series, which recently launched its first ethnography in graphic form, Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution, by anthropologists Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye.

The collaboration has included the participation of Dr. William Flynn who is helping with the visual conceptualization – that is, the translation and adaptation of written research work into a storyboarded version – and Débora Santos a Brazilian graphic artist who is illustrating the work (I have very limited drawing abilities!). The graphic novel is still in the making. It has been partially funded by a SSHRC Insight Development Grant and under advance contract with the University of Toronto Press, as part of its EthnoGRAPHIC series, which recently launched its first ethnography in graphic form, Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution, by anthropologists Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye.

Gringo Love is different from Lissa in many ways. I read Lissa eagerly given the very few existing ethnographies in graphic form, fascinated by our very varying approaches. Lissa is based on the juxtaposition of two distinct ethnographic research contexts: kidney transplants in Egypt (Hamdy), and genetic breast cancer testing in the United States (Nye). The story is entirely fictionalized, including the friendship between the two main characters, Layla and Anna, across class, cultural, and religious differences, and the difficult medical decisions they each face. Hamdy and Nye understood well the power of the medium to do something other than that of a conventional ethnography. The comics format works to engage readers through the complex ethical choices facing the two main characters, who are composites, rather than based on real people. It is not the story of an anthropologist, nor does it seek to render the integrity of ethnographic fieldwork – which is perhaps closer to my aim. The story instead carries key themes and issues that emerged in their respective research contexts; we understand that medical decisions do not operate in a vacuum, that the political economy of health and its inequalities, global pharmacology, and the social contexts in which people find themselves mediate medical decisions.

Gringo Love attempts to do something else. It is based on “real” women with whom I conducted research and the story, while fictionalized, draws on my experiences, encounters, and engagements during fieldwork in 2007-2008 and 2014. The graphic story is an attempt to retell what I have learned, mediated by my positionalities, standpoints, and orientations. Initially, I thought of the medium as another way to represent ethnography and I aimed to render, as much as possible, the integrity of the fieldwork. I wanted to leave readers with an impression of what Ponta Negra felt like, for women engaging in practices associated with sex tourism. I constructed a narrative arc based on real events in which I filled in the characters I knew, drawing extensively on interview excerpts and fieldnotes from my observations. I resisted departing too much from what I had observed and understood – an aspect that has remained key to the project even if I have moved more and more towards fictionalization in the process of making Gringo Love. Now the project resembles more a collage or a montage, and I feel uncertain about the extent to which I have preserved the individuality of the people upon which I based the project. While I keep returning to what the women I intend to depict would say or do, the process of creation has necessarily resulted in fictionalization. To build a coherent narrative, I have juxtaposed scenes, used quotes from private interviews in the context of group conversations, created new dialogues, or modified the timeline of events. The process of fictionalization has not been seamless, and I still struggle (and usually agonize) over how to represent the characters fairly. In the second part of this two-part series, I will reflect on the challenges posed by the juxtaposition of image/text in adapting my ethnography into a graphic form.

Marie-Eve Carrier Moisan is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Carleton University.

Marie-Eve Carrier Moisan is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Carleton University.

Stay tuned for Part Two coming soon.