So you are planning your first Introduction to Anthropology course or you are considering an overhaul of this course. What do you do? In my previous blog post I suggested that you approach the course design from the perspective that you only have one shot to make this course relevant to most students. Know your audience, I recommend. I find that a third or more of my students arrive just to fulfill a social science requirement but, more importantly, almost every student arrives without ever having taken any social science in their K-12 years. Therefore, I tell my students how glad I am that they now have a chance to learn some social science, specifically anthropology. I have one chance to help them make sense of their social worlds—the global village they will live in throughout life. To use this opportunity wisely, I now plan my course carefully.

I used to plan very differently. I solicited others’ syllabi and then perused them, darting past the course description, policies, and objectives sections to focus on the course’s schedule. My main question was “What topics should I cover and in what order?” Have you done the same? If so, it’s logical given that most of us focus on content in graduate school and, unlike our K-12 cousins, we rarely, if ever, take courses in curriculum development and effective pedagogy. The textbooks we use reinforce (or structure) the typical syllabus’ straight-line approach to Intro: begin with the four fields and end with globalization and culture change. In between are 5-700 pages chock full of abstract terms to memorize, strange people and practices to view, and a few really odd-sounding theories to apply to it all. Of this massive amount of content, what will stick in our students’ minds is the oddest of the odd practices, and little else. If I want something else to stick I need to be very deliberate about making my one shot matter.

If I have only one chance to make anthropology relevant to my students’ lives, then I should build my course around the anthropological knowledge and understanding they can use throughout their lifetimes. That’s my overarching goal; to achieve this goal I need to identify the most important material, and build the course from end to beginning (“backwards design”) so it will stick. Here are the basic steps I take…

The first step is prioritizing content. Hundreds of pages of textbook content will not stick, so pare back to what you want to last your students a lifetime. I favor sticky analytical frameworks over specific topics or content. For example, my main Intro mantra is understanding culture as comfort—how we acquire cultural practices and ideas in early childhood that become comfortable and comforting to us, yet discomforting to others. To see culture, then, we need to get outside our cultural comforts, to deliberately expand into discomfort zones. Then I build culture as comfort/discomfort into every “topic” I cover. So, for example, when studying communication, students must experiment with breaking unwritten rules about proximity while talking, types of touching behaviors, etc. When studying rituals, we practice rituals of reversal and talk about how it feels both to step beyond our ritual comforts and to return to our comforts.

Next I figure out what knowledge students need as foundational to other knowledge and understanding so that the course is built in layers that all support each other. Too complex to explain fully in one blog post, I’ll give a single example. I spend a long time explaining how people socially integrate into our groups (becoming “us”) before I emphasize how becoming “us” simultaneously creates “others.”

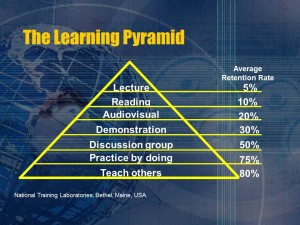

Another critical step is building into the course as much doing as possible. It is now common knowledge that our learning is deepest when we actively participate in it (Ambrose et al. 2010; Bain 2004; Seels 1997). Although there is variation, in general far less sticks when we are passive recipients of others’ wisdom. Research shows that most people are hands-on learners while most faculty members are abstract learners (Felder 2002 [1988]). In this big mismatch our students suffer unless we change our pedagogical approaches. Lecturing sticks least so I avoid it and focus class time on different ways to have students actively engage with the content. Stay tuned for my next blog entry to learn more….

Another critical step is building into the course as much doing as possible. It is now common knowledge that our learning is deepest when we actively participate in it (Ambrose et al. 2010; Bain 2004; Seels 1997). Although there is variation, in general far less sticks when we are passive recipients of others’ wisdom. Research shows that most people are hands-on learners while most faculty members are abstract learners (Felder 2002 [1988]). In this big mismatch our students suffer unless we change our pedagogical approaches. Lecturing sticks least so I avoid it and focus class time on different ways to have students actively engage with the content. Stay tuned for my next blog entry to learn more….

Overall, then, my philosophy for the Intro class is “Less is More.” Less content covered, but more deeply learned. In my next blog post I turn to active learning strategies for both face-to-face and online classes. Meanwhile, think about these questions: Five months, five years, or fifty years from now, what do I want to make sure that these students recall/master that makes a difference in how they live their lives? What added value to their educations and to preparing them to be globally-prepared and mindful citizens can and should this anthropology class make?

Remember, most students stumble into our classrooms and we are truly fortunate to get one shot with them, but it is our job to make that shot truly count.

Sarah J. Mahler is an Associate Professor in the Global and Sociocultural Studies Program at Florida International University. She is author of the book Culture as Comfort.

References:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., and Norman, M. K. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bain, Ken. 2004. What the Best College Teachers Do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Felder, Richard M. 2002 [1988]. “Learning and Teaching Styles in Engineering Education.” Engr. Education 78 (7): 674-81.

Lalley, James P. and Miller, Robert H. 2007. “The Learning Pyramid: Does It Point Teachers in the Right Direction?” Education 128 (1): 64-79.

Seels, Barbara (Ed.). 1997. “Taxonomic Issues and the Development of Theory in Instructional Technology.” Educational Technology 37 (1): 12-21.