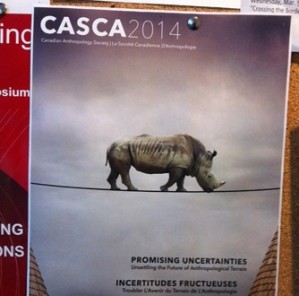

The cupcakes have been eaten, the rhino gone to bed, and CASCA 2014 (#CASCA2104) has come to an end. This year’s organizers should be proud of the stellar lineup they put together. Conference-goers had plenty of options to keep busy.

After all was said and done, though, it was ethnography that kept emerging as the major preoccupation of the conference—what is it, how does one do it well, and, in the end, does it matter? At the Transforming Landscape of the Ethnography roundtable, sponsored by the University of Toronto Press and the Centre for Ethnography at the University of Toronto, authors and editors traded stories about the challenges involved in writing ethnographies and teaching them in the classroom. Some wondered if student concern and confusion over methodology meant we have failed in teaching them what ethnography really is. Others lamented the reputation of ethnography as being “fuzzy” outside of anthropology, while noting that the ethics regime that has taken hold makes participant observation sometimes impossible to undertake.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom, however. While challenges abound, there was an expression of excitement about the ongoing importance of ethnography both within and outside of anthropology.

In a session on Storytelling and the Ethnographic Imagination (see the full schedule here), a packed audience watched four panelists experiment with more creative approaches to presenting their ethnographic fieldwork. All admitted the shakiness of the ground they stood on as they left behind more traditional academic presentation formats, and one even admitted the desire to return to that format even as she raged against it. Anthropologist-turned-fiction-writer Camilla Gibb posed the hardest question of all: Is it even possible for anthropologists to reach a hybridized state where the line between ethnography and fiction is effectively blurred, or is the project doomed to fail? Gauging by the animated responses from the audience, there is clearly lots of energy to keep pushing at the edges of traditional ethnographic writing. We’re at a juncture where experimenting with the form has become more acceptable—even for young scholars seeking tenure—and telling stories differently might help anthropologists reach broader audiences, including the communities they study.

But it was Didier Fassin who addressed the uncertain promise of ethnography most directly in his keynote speech. He located ethnography between science and literature—more inductive and interpretive than science (although still rigorous on its own terms), but more explanatory and morally grounded than literature. Fassin called for a critical ethnography—one that mobilizes history and sociology, not cosmology or ontology, in order to politicize it, and make it relevant in the broader world.

Whether it’s rigorous, historically and sociologically grounded, or slightly unbound in more creative manifestations, ethnography remains essential to the discipline, and one of our most important tools. After thirty years of interrogation and reflexivity, it’s time to re-engage and celebrate the promise of this unique form.

Anne Brackenbury, Anthropology Editor